Complex Structure and Panarchic Resilience

Distinction between "complicated" and "complex," why that matters for innovation, and how can we design more resilient systems.

Updated

Keywords

Systems Thinking, Resilience, Network Theory, Innovation Ecosystems

Introduction

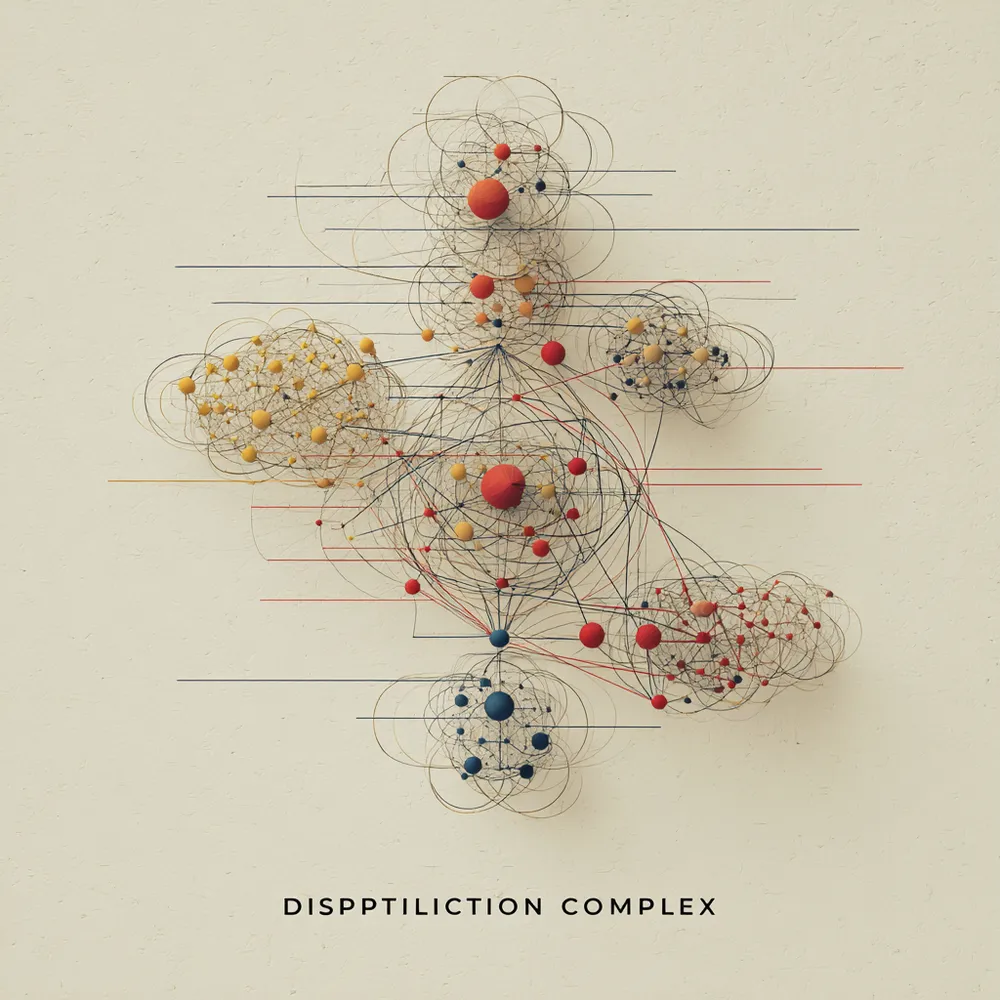

We have a dangerous obsession with connection. In the digital age, we view the “network” as the ultimate good, i.e., the more connected nodes, the better the system. We look at a visualization of a global social network or a bustling startup ecosystem, see a dense web of lines connecting everyone to everyone, and we think: “Wow, that’s complex. That must be robust.”

We are mistaking a hairball for an ecosystem.

In systems theory, there is a counter-intuitive truth: Visual density is often a mask for structural simplicity. And in that simplicity lies a profound brittleness that threatens our organizations, our markets, and our future technologies.

The False Complexity of “Connect All”

Consider a graph where every node is connected to every other node. To the eye, it looks incredibly intricate, as a massive, impenetrable web. But to a mathematician or an information theorist, this system is trivial. Its description length is short and simple: “For n nodes, connect all.”

Because the rule governing its structure is simple, its behaviour is dangerously predictable. In a fully connected system, there are no “firebreaks.” There is no distance. A disturbance introduced at one node, e.g., a computer virus, a banking panic, or a viral outrage, propagates throughout the entire network.

This isn’t Complexity; it is merely Complicated.

- Complicated systems (like a watch or a fully connected server rack) have many parts, but if one key component fails, the whole thing seizes up. They are fragile.

- Complex systems (like a forest or an immune system) have modularity. They can sustain damage to one part without collapsing the whole. They are resilient.

When “Efficient” Networks Fail

We see the failure mode of “naive density” playing out in real-time across our society.

Take Social Media. Platforms like X (formerly Twitter) flattened the topology of human communication. By removing the friction of geography and social circles, they created a “fully connected” graph. The result? Hysteria and outrage spread at the speed of light. There are no local communities to act as buffers or “dampeners” for bad ideas. The system is manic because it is too connected.

We see the same brittleness in Venture Capital bubbles. When an innovation ecosystem becomes too “efficient.”

when every VC reads the same newsletters, goes to the same parties, and chases the same hot deals the network topology collapses into a single node.

This isn’t an ecosystem; it’s Groupthink. This leads to correlated risk. Instead of a diverse portfolio of distinct bets, the entire asset class moves as a “Lemming massive,” rushing over the cliff together. The “efficiency” of the network ensures that when the bubble bursts, it takes everyone down.

Panarchy: The Architecture of Resilience

How do we design systems that are actually complex, rather than just messy? We look to ecology, specifically the concept of Panarchy.

Panarchy describes how resilient systems are organized into nested levels of speed and size. They don’t just have connections; they have structure.

- The Small and Fast: Above ground, you have the “underbrush” of short-lived experiments, rapid mutations, and quick failures. In an economy, these are startups. They are supposed to fail. Their death releases resources (talent, capital) back into the system.

- The Large and Slow: Below ground, you have the “root systems” and the soil composition. These are the long-lived institutions, laws, and cultural norms. They change very slowly. They provide the memory, the anchoring, and the nutrient reserves that allow the forest to survive a storm.

The genius of Panarchy is that it insulates the whole from the parts. It allows for Local Collapse to prevent Global Collapse. A forest fire can burn out the dead wood in the underbrush without destroying the ancient redwoods.

In a fully connected “hairball” system, you can’t have a local fire. You only get the inferno.

”So What?”: Designing for Friction

This distinction matters because we are currently building the digital and organizational operating systems of the future on the wrong principles.

As we architect AI Agent swarms and “frictionless” corporate structures, we are inadvertently designing for total collapse. We are optimizing for speed of connection rather than resilience of structure.

If we want to build systems that survive the next crisis, we need to stop worshipping density. We need to start designing modularity. We need to reintroduce designed “firebreaks”, buffers of time, space, and distinctness that prevent a single bad actor or bad idea from infecting the whole.